~

In the spirit of the Kaggle revolution, an industrious and risk taking hedge fund put their investments in the hands of the public. A hedge fund at the site http://Numer.ai has spent their time to encrypt their proprietary data and present it to the public as a clean, orderly, and clear classification problem. They even clearly label their observations as either training or validation observations. This is important because of the temporal nature of stock data. Can’t train on the future and classify the past.

I decided to take this opportunity to investigate some classifiers I haven’t had the chance to look into yet: XGBoost, and ExtraTrees. In addition to this I wanted to dabble in more ensemble techniques. In particular I look into averaging and rank averaging.

Averaging and Rank Averaging rely on the AUC score measurement. This is also how Numer.ai and most other competitions score your data. So before anything I’ll review the AUC score and the value it holds.

Understanding The AUC score

The Area Under Curve Score, or AUC Score, is an extremely useful - and a bit esoteric - scoring metric. Of course we understand the Accuracy Score intuitively. Count the number correct and the number incorrect, and find a ratio. But what if 85 out of 100 points are labeled ‘1’ and 15 out of 100 are labeled ‘0’. An imaginary classifier may make a simple rule to label all points as ‘1’. You get returned an accuracy of 0.85. This is pretty good right? Wow, I got 85% accuracy with my algorithm.

Unfortunately, you misclassified 15% of the data. What’s worse is you misclassified every single observation labeled ‘0’. This brings us the the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve, or ROC curve.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Receiver_operating_characteristic#/media/File:Roccurves.png

-

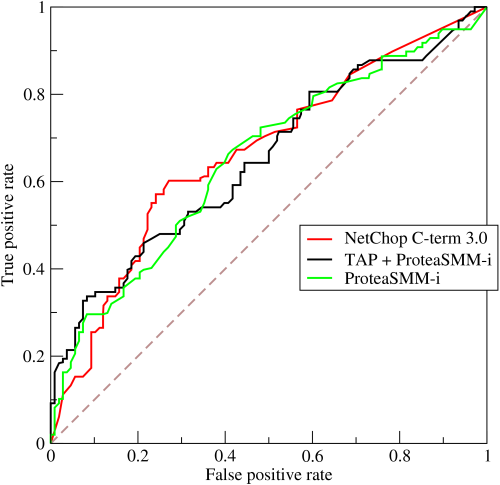

This graph plots false positive rate vs. true positive rate. So false positives are when the classifier labels items as ‘1’ when they are a ‘0’. We would have a lot of false positives with our classifier that only labels observations as ‘1’. In fact the false positive rate would be 1.0. The true positive rate would also be 1.0. This doesn’t feel quite right, but how do we quantify this relationship?

Area Under Curve! We calculate the Area Under the Curve of the ROC curve. If both the true positive and false positive rate are 1.0, then the curve is a straight line. This would get us an Area Under the Curve of 0.5. Our AUC score is 0.50!

Compare this to our accuracy score of 0.85. We were so proud, but we truly did quite terribly. A perfect AUC score would be 1.0, which corresponds to 100% accuracy and 0% false positives rate.

This metric is immensely helpful and worth understanding.

A Quick Cleaning

I expected there to be the normal amount of clean up duty with this data-set. Really there was little to nothing to worry about. There are 14 numerical columns, 1 categorical column, a validation column that flags for use in training or validation, and a label column (target).

Looking at the data, there are enormous numbers being thrown around in some of these columns. Scaling was an obvious first step. I used a logistic regression with and without scaled data and found a very noticeable improvement to scaled data. I then used the get_dummies function to get categorical columns.

#read

datframe = pd.read_csv(path, header=0)

#scale

num_columns = datframe.columns[:14]

np_dat = datframe[num_columns].as_matrix().astype(float)

scaled = preprocessing.scale(np_dat)

datframe = pd.concat([pd.DataFrame(data=scaled, columns=columns),

datframe[datframe.columns[14:]]], axis=1)

#get dummies

datframe = pd.get_dummies(datframe, prefix="", prefix_sep="", columns=['c1'])

#split

val = datframe[datframe.validation==1]

train = datframe[datframe.validation==0]

val = val.drop('validation', axis=1)

train = train.drop('validation', axis=1)

y_train = train.target

y_val = val.target

x_train = train.drop('target', axis=1)

x_val = val.drop('target', axis=1)

In addition to these I tried to find any outliers in the data. I used PCA to visualize and found no obvious outliers.

I then ran elliptical fold outlier detection on the data just to investigate.

After classifying on both the data before outlier detection, and after, there was no noticeable advantage.

Ultimately this only shows how clean this dataset really is!

#General Classification

I used two classifiers I haven’t used before on this problem: ExtraTrees, and XGBoost. Both have a lot of mileage on some very ambitious and successful classification solutions.

As a disclaimer, my scores were based on the training and validation data. The tournament high score at the time was an AUC score of 0.555.

ExtraTrees are a form of Decision Tree ensemble that takes randomness a tad further than the Random Forest Classifier. The Extra Trees also randomly determines thresholds for tree splits and creates many more trees. This has the advantage of further reducing variance, while also slightly increasing bias.

XGBoost is a gradient boosting algorithm used in nearly ever Kaggle winner’s stack of algorithms. It is a boosted tree implementation that is heavily optimized and extremely fast. It takes numpy matrices. In my generalized model for training and testing functions, I used the as_matrix functions on the data frames.

Both the Extra Trees algorithm and the Random Forest performed terribly without optimization. Each getting an AUC score of 0.50. After a grid search they performed better then any other algorithm.

| Classfier | Accuracy | AUC Score |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.532 | 0.538 |

| Extra Trees | 0.529 | 0.538 |

| Logistic Reg | 0.524 | 0.535 |

| SVM | 0.532 | 0.537 |

| XGBoost | 0.529 | 0.535 |

-

Each optimized algorithm got about the same results. The lowest accuracy was Logistic Regression, but we can see that the AUC score was quite comparable. This implies less false positives, despite lower overall accuracy.

When compared to the leader we do not appear so far behind.

Democracy Voting, Averaging and Rank Averaging

A simple way to improve our model is to ensemble. Ensembles attempt to lower variance through combining the predictions of multiple models. There are many ways to do this, I tried three: democracy based voting, averaging, and rank averaging.

For each of these models I created a helper function that creates a data frame from each model’s predictions. For voting we need the predictions. For averaging, we need prediction probabilities:

def get_prediction_df(model_list, x_val, type='auc'):

predictions = []

for model in model_list:

if type == 'auc':

pred_auc = model.predict_proba(x_val.as_matrix())[:,1]

pred_auc = pd.Series(pred_auc)

predictions.append(pred_auc)

else:

pred = model.predict(x_val.as_matrix())

pred = pd.Series(pred)

predictions.append(pred)

predictions = pd.concat(predictions, axis=1)

return predictions

How voting based ensembles work is fairly intuitive. if 3 out of 5 models label the observation as ‘1’, then it is ‘1’. It is a majority vote system. Where one algorithm may have mis-stepped, the others may have been inline. The dangers here are if most models make the same mistakes in the same way. This is where the correct answer will be outvoted, by inherent bias in most models. The other is that if models are correct in the same way there will be no advantage.

for example:

model 1: 010101 3/5

model 2: 011101 4/5

model 3: 001010 2/5

voting: 011101 4/5

if the answer is that all 6 should be ‘1’, the voting model doesn’t improve over your best algorithm! In addition to this only one of the two miss-labeled observations were guessed correctly and that was only by model 3. So clearly there are advantages, and disadvantages to this method. Also, this method only takes accuracy scoring.

The greatest advantage to this method is if you have a very strong model and weight that model very highly. The strong model votes out all the others, unless the other classifiers are very confident the strong model is incorrect.

def voting_ensemble_prediction(model_list, x_val, y_val):

'''

create a voting ensemble from a model list

unweighted domacracy vote

'''

predictions = get_prediction_df(model_list,x_val, type='pred')

results = []

for i in range(len(predictions)):

choice = Counter(predictions.iloc[i]).most_common(1)[0][0]

results.append(choice)

results = np.array(results)

print(accuracy_score(y_val.as_matrix(), results))

Averaging is a more nuanced method. It averages the probability scores for each observation between all of your models. You can think of this as smoothing out of the decision boundary of your algorithms. It most explicitly decreases the variance of the models. It finds the average between probability scores with potentially high variance between models. This is much more robust than voting methods.

def averaging_ensemble_prediction(model_list, x_val, y_val, ranks=None):

'''

averages probability scores of multiple models

smooths out decision boundary of ensemble

if ranks are sent average rank is determined

'''

## this is used for rank averaging

if ranks is not None:

ranks = ranks.mean(axis=1)

pred_auc = preprocessing.normalize(ranks)[0]

else:

predictions = get_prediction_df(model_list, x_val)

pred_auc = predictions.mean(axis=1)

print(roc_auc_score(y_val.as_matrix(), pred_auc))

return pred_auc

What happens when one algorithm has prediction probabilities that are close to 0 and another has probabilities close to 1? There could be huge costs to having the algorithm give greater weight to algorithms with higher prediction probabilities despite having the same overall rank of the result. To get rid of this cost we can first rank the prediction probabilities and then average them. This removes outliers, and high probability generating models. After the ranks are averaged they are normalized between 0 and 1 to match probability predictions.

def rank_averaging_prediction(model_list, x_val, y_val):

'''

creates dataframe of probability score ranks

sends the data frame to avaraging_ensemble_prediction

for auc scoring

'''

predictions = get_prediction_df(model_list, x_val)

ranks = []

for col in predictions.columns:

rank = pd.Series(stats.rankdata(predictions[col]))

ranks.append(rank)

ranks = pd.concat(ranks, axis=1)

averaging_ensemble_prediction(model_list, x_val, y_val, ranks)

So what are our results!? The score will be an Accuracy Score for the voting ensemble and an AUC Score for the averaging ensembles

| Ensemble . | Score |

|---|---|

| Voting | 0.530 |

| Averaging | 0.543 |

| Rank Average | 0.544 |

-

This is way better!!

Our voting ensemble didn’t do quite well. Our Random Forest and SVM actually performed better. Despite this, we have sizable increases for our averaging models. We can infer that there was not too great of variation between prediction probability ranges between our models. We can see this because of the marginal increase between the standard averaging model and the rank averaging model.

Take-Away

When using the Rank Averaging algorithm on the tournament data, we get an AUC score of 0.5375. At the time it was good for 28th place out of 204. By now I am sure it is bumped far lower.

We can see the benefits of variance reduction using ensembles. This increase in reliability and success can be seen in creating ensembles of many many more models than I used. Some ensembles have hundreds of models within them.

Next time I would like to experiment with stacking and blending to further increase my scores in prediction.

Check out full code at github.com/agatorano

2016: Andre Gatorano